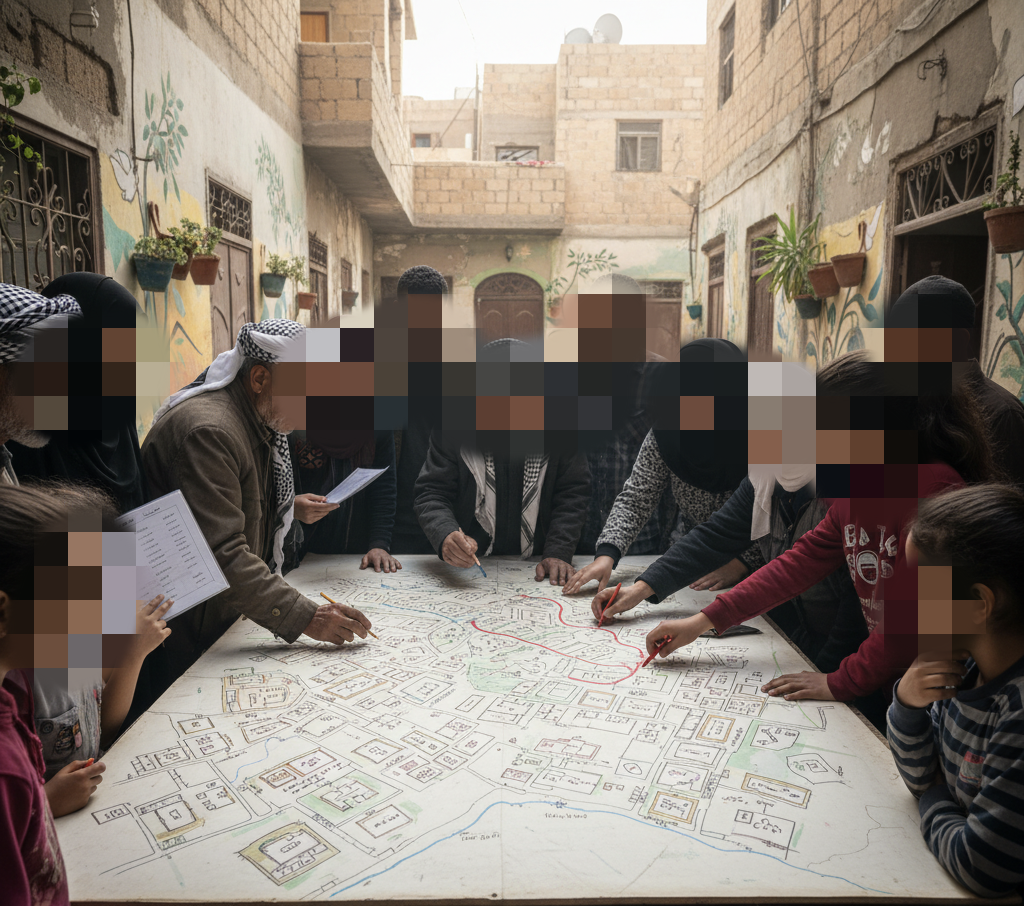

Trust grows when people can point and say: “That is my building. That is my lane. Those are our names.”

Following (1) From Ruin to Spatial Justice and (2) Debris as a Beginning, this essay looks at the quiet heart of recovery: how people know they can come back to their place—and be seen there.

When a city restarts, the first promise it must make is simple: you can return to your own neighborhood. Not to a generic block, not to a distant site with a nice plan, but to the streets that still carry your family’s footsteps. That promise is made with maps, signs, and small acts of recognition. It is also made with the way we talk to people about where they belong.

In Gaza, many homes were known more by family names than by parcel numbers. Memory was the address. After war, memory needs a bridge. That bridge can be modest: a neighborhood map on the school wall; street names painted again; door numbers fixed; a notice that lists who lives in which building and which entrance. None of this is glamorous. All of it tells people: this place remembers you.

Legal tenure is complex and will take time. Life cannot wait for the last stamp. A clear interim rule helps: a household’s right to remain in its neighborhood is acknowledged now, while the legal file is resolved in parallel. People receive a simple proof of occupancy tied to a point on the map—household to address, address to block, block to neighborhood. The message is plain: you are not being moved away by accident of paperwork.

Good maps come from the ground up. Walk the streets with residents. Ask them to draw paths to the clinic, the market, the bus stop, the mosque, the sea. Mark the shortcuts, the places that flood, the corner where children cross. These are not doodles; they are the operating manual of daily life. Put the results back in the open: a weekly map at the school, a printed sheet at the market, a WhatsApp image that anyone can forward. Rumor shrinks when a city posts its own answers.

Mistakes will happen. Names will be misspelled; lines will be off by meters; two families will claim the same doorway. What matters is not perfection but a visible way to fix errors. A desk that receives corrections, a phone number that returns calls, a small team that visits and adjusts the map. People accept waiting if they see the wheel turn in public.

“Planning” often tries to straighten what real life made curved. Resist the temptation to prove order by drawing harder lines. A plan that erases a courtyard to widen a road may look neat on a wall and feel cruel on the ground. Keep families within walking distance of their kin. Keep street names that carry history. Adjust gently where safety demands it; otherwise, let neighborhoods recognize themselves when they look in the mirror.

Return also needs anchors—places that tell a district it is alive again. Schools, small clinics, and markets do this better than any slogan. Put them back early and connect them with clear, safe paths. If a child can reach class without wading through mud; if an elderly woman can reach the nurse in ten minutes; if bread is bought around the corner—then the map is not only a picture. It is a working promise.

There is a second kind of mapping to protect: time. Measure how long it takes to reach water points, a bus stop, a pharmacy. Publish those times and try to shorten them month by month. Travel time is not a technical detail; it is dignity. It decides whether parents keep jobs, whether girls stay in school, whether a fever becomes an emergency.

None of this requires heavy technology. Paper maps, paint on walls, printed lists, a simple online viewer—each can carry trust if the city updates them often and in public. Trust grows when people can point and say: “That is my building. That is my lane. Those are our names.”

In the end, mapping return is not cartography; it is care. It tells people they do not have to start their lives over in a place that does not know them. It gives neighborhoods permission to remember—and to become legible again to themselves. If Gaza can do this early and plainly, the later choices about housing and infrastructure will rest on solid ground: not just soil and stone, but recognition.